This contemporary art exhibition features three artists who, at intervals between 2019-2021, have engaged critically with the archive and collections of the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. Attracted by their bold and irreverent attitude, the curatorial team of the project Ongoing Africa (Michael Barrett and Andrea Davis Kronlund) approached three visual artists Diana Agunbiade-Kolawole, Andreas Nur, and Theresa Traore Dahlberg. They are among the co-founders of the collective platform OUFF.* Although the museum approached them as part of a collective, the artists chose to make individual journeys—guided by their artistic visions and personal biographies.

Despite the challenges of an unprecedented historical period—charged by the BLM movement and severely circumscribed by the global pandemic—the work of Agunbiade-Kolawole, Nur and Traore Dahlberg in the museum resulted in diverse forms of expression ranging from video, audio, sculpture, and photography. Taking as points of departure established art forms like advertising, collage, and oral history, the three artists created intriguing ways of experiencing memory, style, places, colonialism, desire, and the often-winding migration histories of the African diaspora.

They employed an array of techniques such as still life photography, video collage, and brass casting to probe and dialogue with the materiality of historical artefacts and photographs. The ethos and aesthetics of remixing—to grasp something old to shape it into something new and making it your own—was a notable feature of the resulting works. Remixing points to possible future uses of the museum and the historical material charged to its care.

Before using the Museum of Ethnography’s collections, the three artists had to contend with the loud, authoritative voices of those who brought the artefacts and photographs to the museum. In this case, collectors include Ekman (sea captain), Bolinder (ethnographer), Kjersmeier (poet and connoisseur), in addition to numerous photographers (missionaries, travelers, colonial administrators). Frequently, their knowledge of the uses, functions, and original contexts of the objects were lacking, something the museum also failed to redress over the years. By inscribing into the museum catalogue their limited understanding, the collectors seem to drown out the multitude of personal experiences, world views and life trajectories embodied by the objects in their original context.

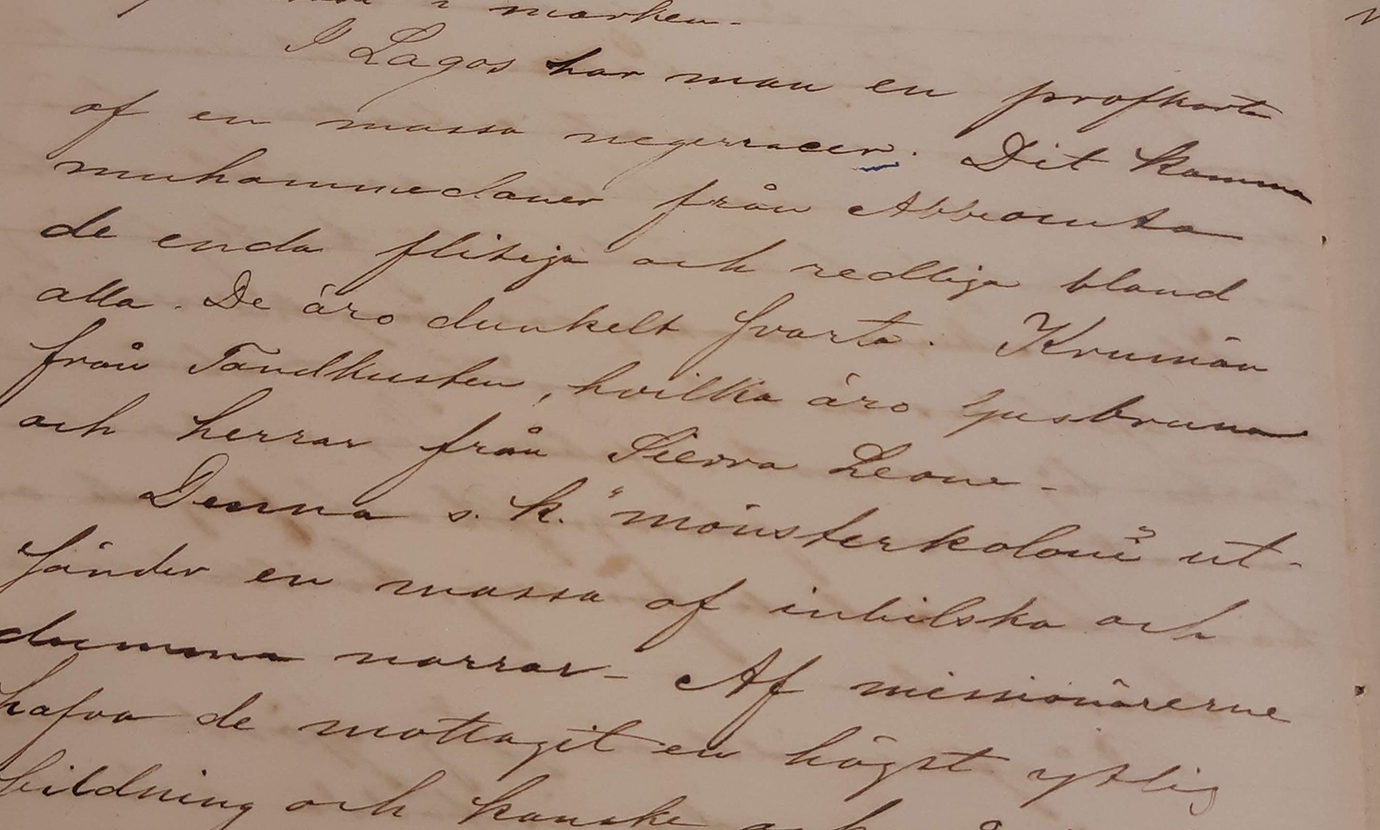

Entry written in Lagos 1869 in the diary of Gustaf Henrik Ekman (1848-1870), Landsarkivet, Göteborg.

Entry written in Lagos 1869 in the diary of Gustaf Henrik Ekman (1848-1870), Landsarkivet, Göteborg.

Very few European collectors before African independence bothered to name artists and makers—sometimes their ethnic belonging would be mentioned—thus inserting themselves as agents of the artworks and artefacts.

Remaining were the sweeping and often racist judgements of the qualities and customs of African peoples. As these descriptions and representations linger in the museum catalogue, the result is an often-expressed view from visitors, especially those of African descent, that the museum’s presentation of Africa is toxic, paternalistic, and demeaning. The artists demonstrate that there are a multitude of creative ways to respond to such narrow views of the African past, present, and future.

*The collective OUFF also includes Afrang Nordlöf Malekian, Francine Agbodjalou, Cristian Quinteros Soto, Ehab Aljabi and Samuel Girma. It began among POC students at the Royal School of Art in Stockholm.